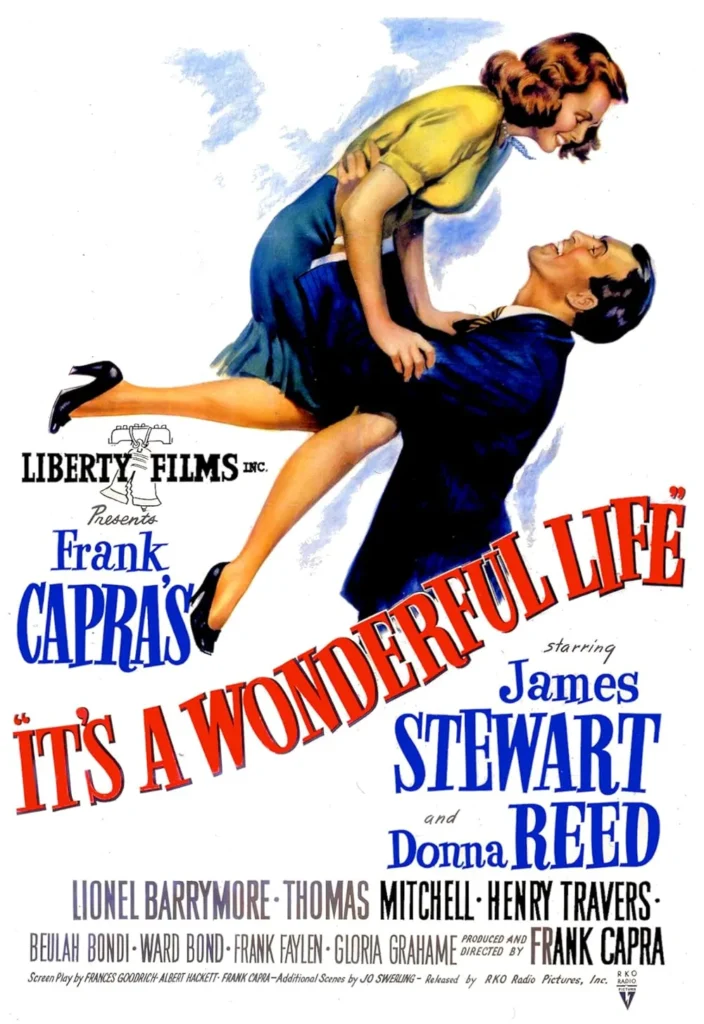

In the frost-bitten wasteland of Bedford Falls, “It’s a Wonderful Life” unfolds as Frank Capra orchestrates what might be the most beautifully warped holiday tale ever committed to film. This isn’t just some quaint Christmas story – it’s a descent into madness, a psychological thriller dressed in holiday garb, where one man’s existential crisis becomes a cosmic battle for his soul.

James Stewart’s George Bailey stands before us like a man possessed, his face contorted in anguish as he contemplates the void beneath Suicide Bridge. The snow falls like ash from heaven, and in this moment, we’re witnessing something raw and primal – the complete psychological breakdown of the American Dream itself. Stewart doesn’t just act this role; he bleeds it. His performance is a masterclass in slow-burning desperation, each thwarted dream and sacrificed ambition carving new lines into his face until that final, terrible Christmas Eve when it all comes crashing down.

But let’s rewind this nightmare, shall we? Because before the darkness, there was light. We watch young George Bailey, this kid with fire in his eyes and wanderlust in his veins, dreaming of building cities and spanning continents. He saves his brother from drowning in an icy pond – losing his hearing in one ear, gaining the first of many scars that will mark his journey. Then there’s the moment in the drugstore, where he prevents the grief-stricken Mr. Gower from accidentally poisoning a child. Already, the pattern emerges: George Bailey, the reluctant savior, sacrificing pieces of himself for others.

Capra, that magnificent bastard, builds his trap slowly. Every time George tries to escape Bedford Falls, the town wraps its tentacles around him tighter. His father’s death? Chains. His brother’s marriage? More chains. The banking crisis that devours his honeymoon money? Golden handcuffs forged in the fires of responsibility. Even love – pure, devoted love in the form of Donna Reed’s Mary – becomes another beautiful anchor holding him in place.

The film’s antagonist, Mr. Potter, played with delicious malevolence by Lionel Barrymore, isn’t just some mustache-twirling villain – he’s the embodiment of cold, calculating capitalism. He sits in his wheelchair like a spider in its web, waiting to devour dreams and foreclose on hope. When he offers George a job with a massive salary, it’s like watching the devil himself extend a contract written in blood.

But it’s in the film’s third act where Capra really starts dancing with the darkness. When Uncle Billy loses $8,000 (a fortune in 1946), we watch George Bailey’s sanity unravel like a cheap sweater. He terrorizes his family, screams at a teacher over the phone, and drinks himself into oblivion at Martini’s Bar. Stewart’s performance here is almost too real, too raw. An absolute train wreck in super slow motion.

Then comes Clarence, the angel who hasn’t earned his wings. Henry Travers plays him with a sort of bumbling innocence that masks something far more cosmic and terrifying. Because what follows isn’t just some Christmas Carol-style morality tale – it’s an exploration of existential horror that would make Kafka proud.

The alternate reality where George was never born – “Pottersville” – is a fever dream of noir shadows and moral decay. Every familiar face is twisted into something grotesque: the kindly bartender becomes a sneering thug, the town floozy ends up in handcuffs, and George’s mother transforms into a bitter crone running a boarding house. It’s like watching an iconic Norman Rockwell paintings melt in acid right before you eyes.

This sequence isn’t just showing George his importance – it’s ripping apart the very fabric of reality to prove that one man’s existence can be the thread that holds an entire community together. The horror in Stewart’s eyes as he runs through the streets of Pottersville isn’t just acting – it’s the genuine terror of a man watching his entire world dissolve into nightmare.

The film’s conclusion, with the town rallying to save George, might seem like a sugar-coated ending after all that darkness. But look closer. The money they raise isn’t just cash – it’s a spiritual redemption paid in dollar bills, every contribution a testament to the invisible web of human connections that George has woven over a lifetime of frustrated dreams and accumulated sacrifices.

When Harry Bailey raises his glass and declares George “the richest man in town,” it lands like a punch to the gut because we’ve seen the true cost of that wealth. It’s measured not in dollars but in abandoned ambitions, in the cities never built, in the places never seen, in all the might-have-beens that George Bailey traded for the lives of others.

Capra’s masterpiece is a haunting reminder that our lives are not our own – they’re tangled up in a vast tapestry of human connections, each choice we make sending ripples through countless other lives. It’s a film that dares to suggest that true heroism isn’t found in grand gestures but in the quiet accumulation of daily sacrifices, in choosing to stay when every fiber of your being screams to run.

The final scene, with Clarence’s bell ringing and George’s daughter delivering that famous line about angels getting their wings, isn’t just heartwarming – it’s a cosmic joke, a wink from the universe suggesting that maybe, just maybe, all our suffering has meaning in some grand celestial accounting.

“It’s a Wonderful Life” remains a masterpiece not because it makes us feel good, but because it makes us feel absolutely everything. The crushing weight of responsibility, the bitter taste of forgotten dreams, and yes, ultimately, the transcendent power of community and connection. It’s a cinematic exorcism of the American Dream, replacing the myth of individual achievement with something far more profound: the recognition that our lives are wonderful not despite our sacrifices, but because of them.

In an age of cynicism and disconnection, this film hits harder than ever. It’s a brass-knuckle punch wrapped in tinsel, a spiritual warfare manual disguised as a Christmas movie. And in James Stewart’s George Bailey, we see ourselves – trapped, struggling, surviving, and ultimately realizing that maybe, just maybe, the life we ended up with is more wonderful than the one we planned.

As the credits roll and Auld Lang Syne fades into silence, we’re left with a profound truth: sometimes the most wonderful life is the one that breaks your heart, again and again, that is until you finally realize that your hearts truly belongs to everyone else.